Posture or “Acture” in tango

Moshe Feldenkrais made-up the word “acture”, to replace the static concept of posture. In the book ”Body And Mature Behavior”, he developed the idea that there is no “correct” posture, but a moving body that must adapt to every situation. The wider the range of possible movements, the more effectively it adapts.

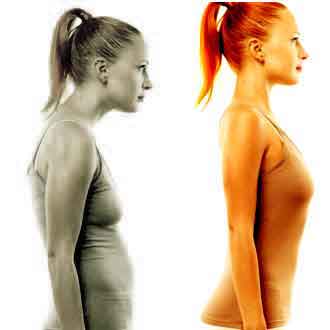

To understand this, imagine someone who is always standing with his back bent and his chin forward: his position is not bad in itself, but the fact that he cannot change it. The extensors in the back of his neck are under constant and excessive strain to keep his head as far forward of his pelvis, and the flexors in the frontal part of his torso are permanently shortened.

Repeating to him: “straighten your back!” is not a solution, because his brain has lost the ability to relax the flexors. With conscious effort, he can (at least partially) straighten his position, counterbalancing the permanent effort of his chest muscles with additional effort of his back muscles. Agonists and antagonists force at the same time, creating an apparently healthier position, but in reality unbearable in the long run, and moreover undesirable because of the pressure it imposes on the joints between the vertebrae.

The Feldenkrais approach would consist of teaching this person extension movements. First small ones, then larger, as she learns to coordinate flexors and extensors, hence achieving them without unnecessary effort. Once she improves her freedom of movement, the idea is to suggest (without imposing it) that she can use it to switch from a curved position to a more upright one.

Not imposing is one of the keys to improvement.

If the person feels forced to violate what he is used to perceiving as a limit, the benefits of relearning the extension may be lost: instead, he will fall back into an ineffective attempt to force the position.

What does this have to do with tango?

Everything!

In my opinion, the application of this concept to the posture sought in tango is brilliant.

It took me a long time to come to this conclusion (starting from the opposite one), and I will share here my path:

Many dancers and teachers promote the idea (static description) that the pelvis is behind the rib cage. Some give a measure of it: the pelvis in line with the heels, the chest in line with the metatarsals. Others just recommend taking it back. For some, this position is that of the woman, while the man is more vertical.

My preferred position is quite close to this last definition, except that the man also has his pelvis behind his chest, the differential is just less.

This organization has the double advantage of allowing a closed and very enveloping abrazo, while safeguarding the independence and freedom of movement of both partners, who can use their whole foot, heel included, to lean on the ground.

But when it comes to teaching it, this position poses problems that are disproportionate to its apparent simplicity.

Most students have their pelvis much further forward than it should be, and their attempts to move it backwards result in painful strains on the lower back. Many European tango teachers, for whom this enigma has remained an enigma, have found an explanation for the fact that they observe such a position in numerous Argentinian dancers, without either themselves or their students being able to reproduce it: the South American butt…

According to them, the women of this continent are physiologically different.

Some of these connoisseurs of the female body are vehement in their condemnation of this posture, which certainly testifies that they themselves have not found the means to adopt it.

And this is understandable if we consider that the closer a joint is to our centre, the less conscious control we have over its movements. We generally have a low level of refinement on the relative movements between ribs and pelvis. The good news is that they can be learned. But I’m running ahead of my story.

I’m not sure how I learned it myself in the first place. I have a few guesses at best. I remember more clearly that when I started to teach tango, I used to propose to my students to walk as a couple, the man holding his fixed forearm in front of his lower abdomen, which pressed his partner’s belly if she did not keep the desired position of her pelvis during the backward step. The man’s arm thus played the role of feedback,enabling the woman to become aware of her position. To a certain extent, it was also a “restraint”, in the sense that it held this position by force.

After a year or two of this experience, I discovered that it was usually much more effective for the partner to circle the woman’s lower back (in the sacrum area) with his hands, applying light pressure, as if to draw her pelvis towards his, and to ask the woman to resist this pressure continuously.

I blamed the success of this exercise on the “spirit of contradiction”: Show something to a student – he will do exactly the opposite!

Then I heard the concept of relative movement, and that some people recommended it to women to compensate for inaccuracies. This approach consists of learning to move the hips backwards in relation to the torso, and using this movement to finish the step in case the trajectory of the abrazo does not otherwise allow the heel to be pushed into the ground.

The results seemed exciting to me. However, I was not at peace with the idea that this movement is only useful to compensate for inaccuracies of the partner. On the other hand, to use it automatically with every step would obviously break the relationship between torso and pelvis, which is the sine qua non for the man to know where the partner’s foot is. And this would result in a pigeon’s gait.

My experience, however, clearly showed the superiority of a movement approach to a postural approach.

The same partner thinking in terms of movement (the hips can move behind the torso to reach the vertical of the heel) had a better abrazo and more anchorage in the ground than when she was thinking in terms of posture (i.e. a fixed relationship between the pelvis and the torso).

At that time, I was not very familiar with the Feldenkrais Method, which I was just discovering, and to resolve the contradiction, I resorted to the concept of micro-movement: it was my way of reconciling the apparent absence of movement with its real presence.

The idea now was to learn the displacement of the hips in relation to the torso by exaggerating, and then to decrease this movement little by little until it became mostly invisible – a micro-movement.

I was sticking to this approach, until about 3 years ago, when I tried a ” a la Feldenkrais” approach to pelvic and torso movement:

Step 1: standing with feet slightly apart, torso fixed in space. Move the pelvis back and forth. Observe the weight distribution under your feet. Observe your lower back. Imagine it stretches as your pelvis moves in the direction of your heels.

step 2: same position. This time the pelvis is fixed and it is your sides and chest that move back and forth. Observe the movement of the pressure under your feet. Imagine that your sternum moves upwards at the same time as it moves forwards.

Step 3: Carry out steps 1 and 2 simultaneously and in opposite directions, coordinating them so that the pressure under your feet remains unchanged during the movement.

My first surprise was to see how hard my students were struggling to perform these tasks: even when dividing the movement into 2 seemingly very basic preliminary steps, many people get stuck for quite a long time either:

.when they think they’re moving the pelvis back and forth, they just tilt it…

. when the pelvis moves backwards, the sternum tilts as if to bend over.

.The lower back muscles make unnecessary strain.

The next step, once movements 1, 2 and 3 become easy and smooth, is to use them to find a more stable position in the dance. One way of proposing it without imposing it is the following:

Exercice 1 On one foot, an assistant gives gentle thrusts to your sacrum as if to tip you towards your toes. Between each push, you slightly change the position of your pelvis in relation to your torso, using the movement described in step 3.

Most people find that a pelvis position further back than they are used to is more stable.

Exercice 2 Same thing with different levels of flexion of the knee. You may be surprised at how much you lose your organization by bending your knee. Once you realize this, there’s nothing stopping you from keeping it.

Exercice 3 The same experience needs to be repeated after each dancing step.

As you rehearse, it is suggested to look for the stable position without waiting for the control thrusts. In this way, this search which started as a movement between the hips and shoulders becomes, little by little, the search for a position.

What does the Feldenkrais approach bring in relation to the idea of micro-movements previously mentioned?

-

It divides the movement to learn into assimilable stages.

In the beginning, that was the only advantage I gave it. However, it is a big one. When I started experimenting on myself with the 3 steps described above (and some additional ones, like doing the same, sitting on a gymnastic ball), I soon discovered tensions in the middle and lower parts of my back, as well as in the region of my upper belly and lower ribs, that I could release to make those moves easier. At first the feeling was just slightly identifiable. No wonder I did not identify it while doing “normal” dancing exercises. The attention is busy with so many apparently more important things !

Nevertheless, within days, I observed a noticeable change in the position that I had considered optimal for my pelvis for years, in favour of a more reclined position.

-

It switches the attention from the goal to the process.

The second advantage seems to me now even more consequent.It is a subtle one When I think in terms of posture or of micro-movements, I set myself an aim. 3 years ago, I reached a better position, and I froze it, by imposing myself to deviate from it as little as can be.In 3 years, my body and my brain changed. But I kept looking for the same position.

The moment I ceased thinking of this position like my goal, but I started to consider that I have at my disposal a set of moves to make myself more comfortable, changes started again to happen.

Maybe 3 years ago, my body had some limits, like this bumpy guy in the beginning: he can not switch in one month from bumpy to straight. But if he goes on learning to extend the spine, he will go on improving, at his own pace. Whereas if after the first improvement, he decides that his new limit is the best he can do, then there is a good chance it will be.

-

-

-

-

/ 0 Comments